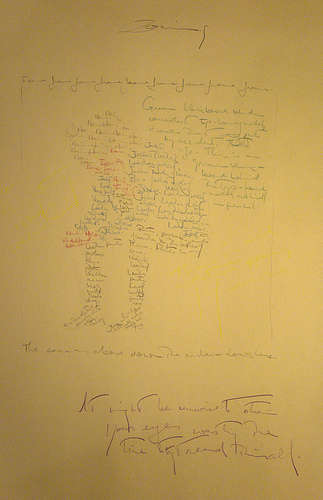

Damn, this word looks hard to digest, doesn’t it? But it appears to have two parts. The first part has two d’s sticking up, and the second part has two j’s sticking down. Both halves have u and n, making them look like they could be rotated, but both have e, which resists rotation unless you’re using phonetic symbols. And the first half has the two o’s, while the second half has an a and an l. So maybe the beginning is really a oupəonp that’s been turned upside down, but the second half, if it’s something upside down, has already been partly digested. Was it punfef? So hard to say.

Well, so is this word, until you get your mouth around it. It’s not really made for taking down in one gulp. Its rhythm is like something from Dave Brubeck – duh-da-DAH-da-de-DAH-da – or (there are two ways to say it) a Mexican hat dance – da-DAH-da-DAH-da-DAHda. But if you say it a few times you will notice that, except for the final /l/, the consonant patterns for each half are practically identical: /d…d…n/ versus /dʒ…dʒ…n/. Again, the second half seems more digested: the tongue, rather than tapping hard and smooth against the ridge, flexes in and releases a bit more gradually.

Fair enough. The first half refers to the duodenum, the first twelve inches of the small intestine after the stomach (the name comes from Latin for ‘twelve’ because it was thought of as twelve finger-breadths). That’s where most of the chemical digestion takes place. The second half refers to the jejunum, the middle part of the small intestine, where a lot of the absorption of digested food takes place. It got its name from Latin for ‘fasting’ because at autopsy it was usually empty – because food passes through it quickly on its way to the ileum and the large intestine. And the place they join is the duodenojejunal flexure (if you say that really quickly, it sounds like it could be some rude dismissal, especially the flexure).

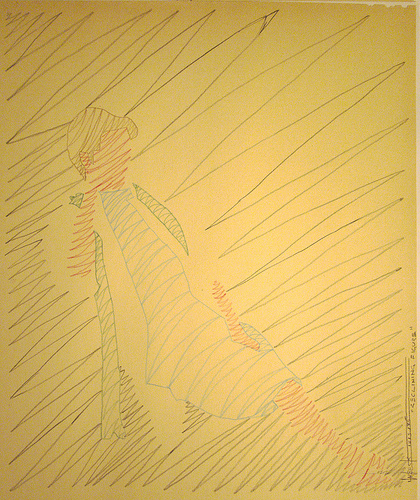

The duodenojejunal flexure hangs below the stomach, a smart little bend. The two parts are continuous but distinct, just like the two parts of this word: the duodenum is up, and the jejunum hangs down – and around and around. Between them they help you be nourished. But the word is better tasting.