Most people who use linchpin these days use it figuratively, to mean someone or something without which the wheels would come off the machine, so to speak. In a pinch, they’ll make it a cinch, even if it’s inch by inch. But what kind of thing might the linchpin of a word be?

Some people will say that it’s the spelling. Take linchpin for example: many people write it as lynchpin. Why? Not because we usually spell the sound that way; all the rhymes are spelled -inch. But there’s one word we have that’s spelled with a y, and it’s lynch, which, of course, is exactly the same sound as linch. The problem being that the verb lynch means ‘execute extrajudicially’ and most often refers to the hanging of black men by white mobs in the American South.

Which, I can assure you, has nothing to do with linchpin. The verb lynch comes from a surname, Lynch, which in England derived from a Kentish word meaning ‘hill’ but was also used as an Anglicized – and modified – form of Irish Loingsigh and related names, which originally named someone who had a fleet of ships. And since neither mob executions nor hills nor ships have anything to do with linchpins, it seems important not to misspell it, less there be a misconstrual.

But in truth, even people who spell it lynchpin don’t seem to consciously relate it to the mob hangings. I suppose they might, if asked about it, speculate that the thing it names was invented by someone named Lynch. But it wasn’t.

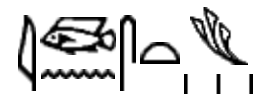

In fact, no one knows who invented the linchpin, because it’s been around since time immemorial – pretty much as long as there have been wheels mounted on axles. When you mount a wheel on an axle, you need to hold it in place so it doesn’t come off. And for that, people historically used what in Proto-Germanic was called *lunaz (the asterisk means we’ve reconstructed it from historical evidence), and in Old English was called lynis, and then in Middle English became lynce or lince: a pin inserted through the axle on the outside of the wheel. By Early Modern English, its spelling had settled on linch (and it’s safe to say that modern people who spell it with a y are unaware of its etymology), but by that time, it had come to be called a linchpin.

Which, given that linch refers to the pin, seems sort of like the number in PIN number or the tea (or chai) in chai tea or the free in free gift. But perhaps it’s more like the berry in cranberry: we could just call the thing a cran because there’s no other cran thing (leaving aside juice blends like cranapple), but somehow we have decided that we want to specify cranberry, just like you’ll sometimes see tuna fish – as though if we didn’t name the kind of thing it is, it would come off its axle and roll loose through the language. So we add the berry in cranberry and the pin in linchpin for a kind of security.

In fact, for linchpin there is a case to be made for the clarification: the meaning of lynis and lynce and linch had, it appears, spread so that it could also refer to the whole axle. It’s like how originally tuxedo referred specifically to a kind of jacket without tails (named after the place it originated), and then the sense spread to the whole suit that included the jacket, and now the jacket itself is called a tuxedo jacket. So why not pin it down with the added specification? Meaning that the ostensibly redundant addition is the linchpin of the word.

And that should hold it – at least until such time as the figurative use becomes the primary one and any literal use is taken as a reference to the figurative sense, at which time we might yet hear “and this is the linchpin pin.” Or we might not – after all, wheels are usually held on by more than a pin these days.