Anise is very divisive.

People are strongly divided over whether it’s delicious or nasty.

They’re also divided over how to pronounce it.

Also, does it have anything to do with Jennifer Aniston?

Let’s start with a key thing: there’s more than one kind of anise. And there are things that are sometimes called anise that really aren’t: fennel, for one, and also star anise, which is not actually related, though it substitutes very nicely and cost-effectively for the original anise. And there are also things that anise tastes like, or that taste like anise, that aren’t anise and aren’t called anise – specifically, licorice (or liquorice, if you prefer). The connection between all of these is cloudy… but only if you mix it with water.

Oh, and there’s also dill. Dill comes into this, just sort of as a little inset. But that’s mainly because of the inscrutability of ancient Egyptians.

Let’s start with the flavour. All of the things that taste like anise, or like licorice, or like fennel, contain the molecule anethole, which really looks like an unpleasant kind of thing to call a chemist, doesn’t it? Anethole is also closely related to estragole, a molecule that gives flavour to tarragon and basil. Anethole is (or plants containing it are) very popular, as we all know, not just for its characteristic and sweet flavour but also because it’s an aid to digestion (and it reduces flatulence too, and not just by overpowering the smell). This made it popular for desserts and after-dinner drinks.

It also has a party trick. Anethole is highly soluble in ethanol (say “anethole in ethanol” five times… after drinking some ouzo or absinthe), but is only slightly soluble in water, so if you dilute a liquor that’s flavoured with it, it goes from clear to cloudy. Which is really cool to observe, and I remember observing it quite a few times one evening in my youth. (I also remember how wretched I felt the next day.) This is called the ouzo effect, but it also affects mastika, sambuca, absinthe, anisette, pastis, anis de chinchón, anís, anísado, Herbs de Majorca, rakı, arak, aguardiente, and Xtabentún. Oh, and I think – I think – Herbsaint.

And if you hate the taste of anise, you’re not going to like any of those – although the amount in, say, a Sazerac is so subtle you probably won’t pick it out. But the funny thing is, you can hate the taste of anethole and yet love the taste of dill.

That’s funny just because anethole comes from the Greek word for ‘dill’.

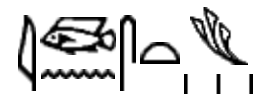

Well. I’m being a bit puckish here. It’s more accurate to say that there has been some historical confusion between anise and dill. It’s not because they taste alike (goodness gracious, they truly do not), but it may be because the plants look similar (they do). The thing is just that there was this Egyptian plant called jnst, pronounced “inset” (see inset for hieroglyphics, courtesy of Wiktionary).

We’re not completely sure what it was, but it was an edible, possibly medicinal, plant with seeds – it could have been anise or dill; Egyptians had both. Anyway, the name made its way into Greek variously, notably as ἄνισον (ánison) and ἄνηθον (ánēthon). This resulted in the Latin words anethum, meaning both ‘anise’ and ‘dill’, and anisum, meaning just ‘anise’. Anethum developed over time into French aneth, Italian aneto, Portuguese aneto and endro, Spanish aneto and eneldo, and obsolete English anet, all meaning ‘dill’ (dill is from an old Germanic root that comes from an ultimately unknown source). And anisum developed into various versions of anis in quite a few languages, mostly spelled anis or anís.

OK, so how do you say anise? I’m not asking “how is it supposed to be said” – I’m about to tell you that. I’m asking how you say it.

Because the thing is, there are actually several ways that are all legitimate, established, accepted: “a knee’s,” “a niss,” “a niece,” “annus,” and “anniss.” Most people I know seem to prefer “a niece.” I, however, grew up saying “anniss,” like the first two syllables of Aniston.

Yes, I know, English got it from the French, so if you want to be true to that origin, you should say it “a niece.” But if we’re going to play that game, I’m going to start calling it “inset,” from the original origin, OK? So lay off. Anyway, I have one more inset to turn to, specifically that actress, Jennifer.

Now, if you know English onomastics, you’ll recognize -ton as toponymic: the family is named after a place, the town (or anyway farmstead) belonging to Anis – well, really, belonging to Ann, probably, and not likely anything to do with anise. But there’s a Greek derivation that’s buried but that we’ll resurrect.

As it happens, Greek for ‘resurrection’ is ἀνάστασις (anastasis). That gave rise to the name Ἀναστάσιος (Anastásios). And that in turn was made into the family name Αναστασάκης, typically rendered in the Latin alphabet as Anastassakis. One person who had that name was Yannis Anastassakis, who was an actor. He was noted for playing Victor Kiriakis on Days of Our Lives – but he did that under the Americanized name his father gave him when he was two: John Aniston. (It was a name that already existed, but usually spelled as Anniston; there are towns of that name in the US.) He, of course, passed that family name on to his daughter, Jennifer.

Sorry for clouding this with that side shot. I know that Jennifer Aniston is not to everyone’s taste. But neither is anise. So there. Take it as a digestif.