This land is your land, this land is my land

From Bonavista to Vancouver Island

From the Arctic Circle to the Great Lake Waters

This land was made for you and me

If you’re not from Canada, you’re probably thinking those words aren’t quite right. But not only are they the words I learned as a kid, I was well into adulthood before I learned that there were American words that were different.

Huh.

The other thing that took me a long time to learn was exactly where Bonavista was. I mean, I could figure out it was on the opposite side of the country from Vancouver Island, but specifically where I wasn’t sure, and for some reason – mainly because the place just never came up outside of that song – I didn’t look it up.

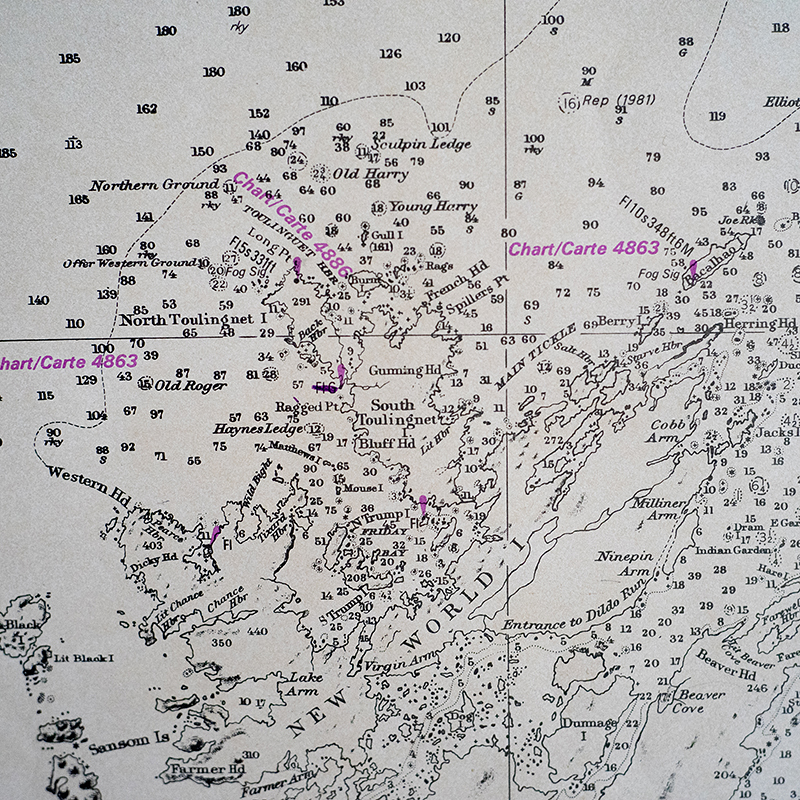

Well, it’s in Newfoundland, on a peninsula about halfway between Twillingate and St. John’s. I still haven’t been to Bonavista. But I have seen many a good vista in Newfoundland. And I feel like doing one more word tasting on Newfoundland.

I’ll assume you can see that Bonavista means ‘good vista’ or ‘good view’ or ‘good sight’ – though, perhaps ironically, Bonavista is not named for the beautiful vistas you can see from it; it is named for being a beautiful sight itself, when seen from sea by an Italian explorer on an English ship in 1497. The story is that Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot, for Anglophiles), on at long last sighting land there, exclaimed “O buon vista!”

Yes, “buon”; bona is not standard Italian or Spanish or Portuguese – it’s Latin (and some regional varieties of Italian). But vista is not Latin; it’s Italian, and Spanish, and Portuguese, in all of which it means ‘sight’ or ‘view’, and in Italian it is also the feminine singular past participle of vedere, ‘see’. The Latin equivalent is visa, the feminine singular past participle of video, ‘I see’ (from which is also derived viso, ‘I behold’, which in turn gave the frequentative visito, which became English visit).

Well, in visiting Newfoundland, my wife and I (and our friends) have seen many sights and views, and good ones at that. There really is no substitute for climbing up on a rocky, mossy, juniper-covered hill and seeing the scene in person, in 360-degree Sensurround. You can watch all the video you want, but seeing just what others have recorded having seen is no substitute.

And of course my photos don’t do it all justice either – but you can take the inspiration and go see it yourself when you have the chance, and if you’re in Canada (or any of several other countries) you won’t even need a visa (though you might want some kind of credit card). And once you have visited and seen these good vistas, they will stay with you as memories, and if you have taken pictures you can revisit them wistfully, at least by sight. The Newfoundland coast really is a good looking place.