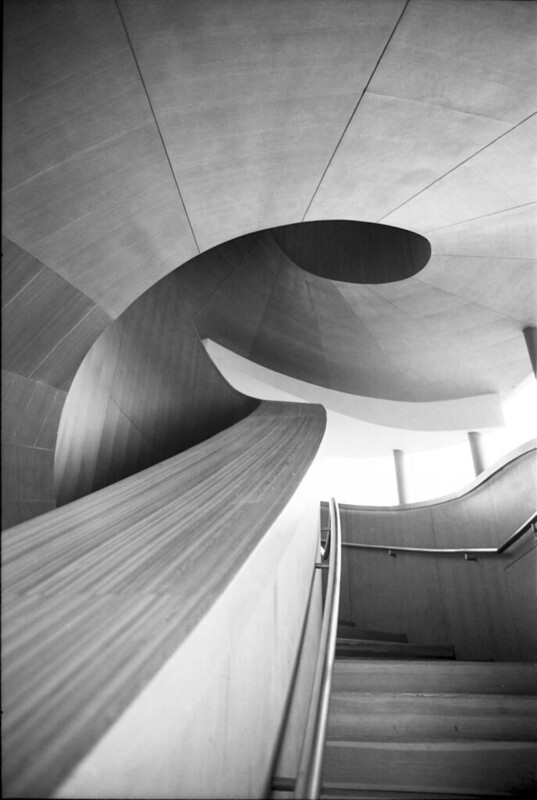

“The Art Gallery of Ontario has a marvellous spiral staircase,” I said to Jess and Arlene as we stood talking at Domus Logogustationis.

“Helical, surely,” a voice from behind me said.

My respiration caught sharply, briefly, and then I exhaled and turned. I found myself facing a fellow I hadn’t met before – evidently a guest of some other member of the Order of Logogustation.

He continued. “A helix has a constant radius, whereas a spiral has a constantly increasing radius. The staircases that are commonly but erroneously called ‘spiral’ are wrapped in a constant radius around an axis.”

I reflected briefly that he had probably never tried calling an architect “erroneous” to their face. I certainly wouldn’t – and especially not Frank Gehry, who designed the staircase I was talking about. “Have you been to the Art Gallery of Ontario?”

“That’s rather beside the point, I’d think,” he said.

“Beside the axis, perhaps. Or the axis is beside itself. The staircase in question is in fact irregular. It is called a ‘spiral staircase’ because that is the term used for the general type, but it is not a perfectly helix or spiral, though I would add that its radius does decrease toward the top.” I pulled out my phone as I was talking and found him a couple of photos I had taken of the staircase in question.

“Grotesque,” he said.

“I suppose it’s not to everyone’s taste,” I replied.

“Literally grotesque,” he said. “As in distorted like a grotto. Grottesco. But not helical and not spiral. It is important to get these things right. I was under the impression that you people here cared about the English language.”

“Oh, we certainly do,” I said, “the way naturalists care about a forest, not the way a florist cares about cut roses. English has been here long before us, it will be here long after us, and it grows through us. It is ever growing.” I moved my finger in an increasing spiral.

“Turning in the widening gyre,” our guest said. “Things fall apart and the centre cannot hold. When a word is given a precise meaning, it is an act of desecration to broaden its use wantonly. It will spiral out of control.”

Jess interjected. “If a child is a certain height when born, does that mean we should cut off its legs when it grows, so that it will never become larger?”

Arlene, who had been busily looking some things up on her phone, joined right after her. “And then there’s the question of what it was when it was born. Neither of these words – spiral and helix – was so strict in its definition when it came into the language, and their definitions for most use cases contain each other.” She had the Oxford English Dictionary definitions in hand, plus some etymology. “Spiral: ‘Forming a succession of curves arranged like the thread of a screw; coiled in a cylindrical or conical manner; helical.’ It’s from Greek σπεῖρα ‘something twisted or wound.’ Helix: ‘Anything of a spiral or coiled form’; helical: ‘Belonging to or having the form of a helix; screw-shaped; spiral.’ It’s from Greek ἕλιξ ‘something twisted or spiral.’”

The guest waved his hand. “Yes, yes, that is why I said ‘when a word is given a precise meaning.’ They may have been sloppy to begin with, but a distinction has been made, just as one has been made between persuade and convince, just as one has been made between less and fewer.” I stifled a snort; my opinion on the subject is no secret. He continued, “Precision in all things. I think you have all heard of the etymological fallacy. We can’t say these words should be sloppy just because in origin they were.”

I nearly coughed at his mention of the etymological fallacy. Was he trying to whack me with my own frying pan? If a word isn’t fixed at its origin – and it is not – how could it be fixed at some other point in time? “And who is it that gives these restricted meanings?” I said.

“Once a definition has been established and accepted in a field or expertise most directly relevant to it, it has gained scholastic authority; it is institutionalized,” he said. “This can proceed variously, but the result is the same: its acceptance grows and grows” – his finger traced a downward helix in the air – “until it is quite embedded. Screwed in, as it were.”

“Within that field, yes,” Jess said, “but specific fields have specific exigencies that more general usage does not. Consider the botanical definition of berry, which includes bananas and excludes strawberries. The term has been pressed into a special use in a way that is viable in a biology lab but not in a kitchen.”

“Kitchens are home to much messy thinking,” the guest said. “If cooks were more mathematical they would produce cleaner, more consistent results.”

More consistently boring, I thought. But I said, “Engineering is mathematical. Architecture is mathematical. And yet engineers and architects still call such staircases ‘spiral stairs.’”

“As they have since the 1600s,” Arlene added.

“They have yet to catch up, perhaps,” our guest said, “but the best use of a word is the most precise.” He traced in the air a narrowing conical spiral. “Meaning increases in acuity over time, as long as we shape it. We just need to get to the point.” He jabbed his finger to make the point.

“I gather,” Jess said, “that you have no use for metaphor or poetry?”

“Stopgaps for the primitive imagination,” he said.

Jess snickered. “Stopgaps. No metaphor there.”

“Well,” I said, returning to the initial subject, “Frank Gehry shaped the staircase in the AGO, and I think it’s a great metaphor for language development: irregular, fascinating, with various twists and turns, and at the top, the point of it all, is… art.”

The guest chortled. “There’s a reason I haven’t seen the staircase in question. Art is simply reality badly rendered.”

I inhaled and was about to form a comment on his artlessness, but I sensed that this was spiraling out of control, or at least descending in a helix to hell. I paused, circling in my mind.

But Arlene got straight to the point. Fixing him with a steady gaze, she spiraled her finger towards the door: “Screw off, you.”