My friends and my wife and I went for an outing from Herring Neck on the rocky coastline of Newfoundland to nearby Twillingate. We walked up and around the lighthouse on North Twillingate Island. Then we took our packed lunch of runny cheese and large crackers and canned fish and hiked up and down and around and over, with a pause to eat, in the vicinity of French Beach on South Twillingate Island.

I adore hiking. I grew up hiking in the Rocky Mountains, and I happily scramble up Newfoundland’s rocky trails between evergreens and scrub brush and past little ponds and streams, and when I am high on a rocky promontory above the Atlantic it is just like being up in the Rockies, on Tunnel Mountain or Sulphur Mountain or the Little Beehive overlooking the Bow Valley, except that the valley has been filled with saltwater up to a couple hundred feet below where I stand. The ocean is a wide, deep valley, so wide I can’t see across it, but somewhere on the other side is a French beach on the mirroring coast of Brittany.

It is all strangely familiar and familiarly strange. When I look at the terrain around my feet I might be on the way to Skoki Lodge or Sentinel Pass or Lake Agnes: there is lichen on the rocks, and juniper, and spruce trees. But then we descend briskly and we are on French Beach with waves smoothing out endless pebbles, a sight seen in my life only on vacation.

On the drive back through Twillingate we pass a two-storey box with teal siding and white doors and windows and the name TOULINGUET INN in hand-cut wooden letters. I ask Sarah what that word is. She says it’s the original name of Twillingate.

I had not, until that moment, considered that Twillingate might have come from anything but English. Yes, twilling (or twillin) is a bit mysterious, but more familiar than strange, and gate is, well, a gate. I was willing to take it at face value. But what was Toulinguet? Was it perhaps the name of a relative of Demasduwit or Shanawduthit, who were among the last of the Beothuk people, who were crowded from the coasts and squeezed to starvation by European incursions?

No, it is a word from the far coast of the Atlantic. The western tip of Brittany reaches towards America at Pointe du Toulinguet, a rocky promontory that, like North Twillingate Island, features a white lighthouse. The fishers from Europe saw this newfound headland and thought this strange land looked familiar, so they named it after what they knew – a mirror Toulinguet. And then when the area was settled by people from England, they made this slightly strange word more familiar: Twillingate.

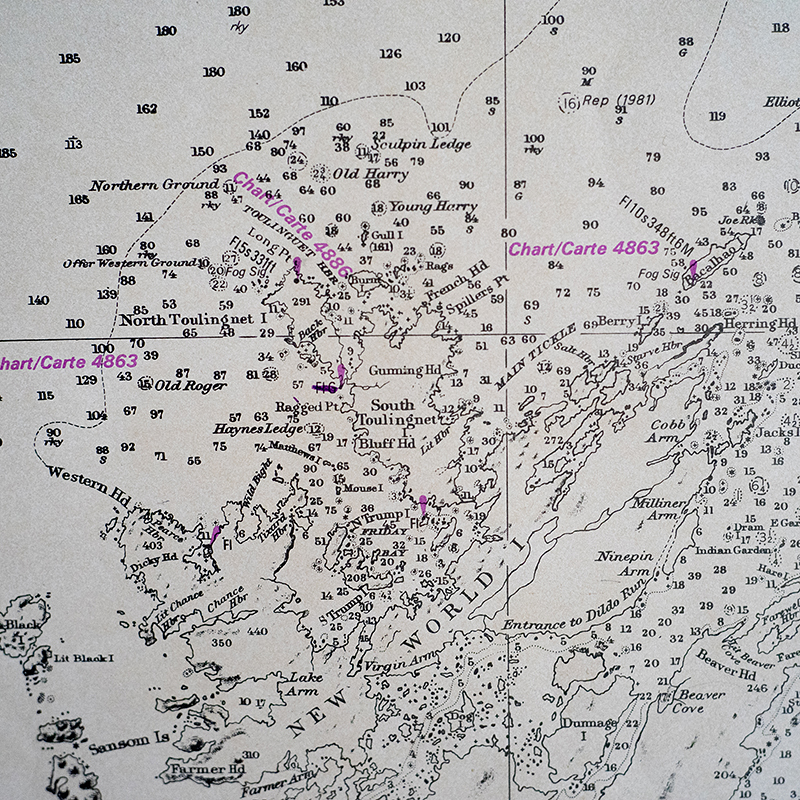

But Toulinguet survives; it has not been forgotten. Sometimes, though, it is made a bit more familiarly strange. A main road across South Twillingate Island, from the causeway from New World Island up to the town of Twillingate, is named Toulinquet Road, with a q before the u. And an old chart that is wallpapered in Sarah’s house makes the name of the islands Toulingnet, as though they went fishing for the name but netted something topsy-turvy, n for u.

But where did Toulinguet come from? It’s a French word, right? We can see that by the spelling. Well, yes, in the same way as we can see by the spelling that Twillingate is an English word. But each word is the meeting of two languages; with Toulinguet the other language is Breton, the Celtic language of Brittany. The Breton source, so I read, is toull inged, meaning ‘plover hole’, for a pierced rock there favoured by birds (though the usual Breton word for ‘plover’ is morlivid, and another source tells me inged means ‘petit chevalier’, the shorebird called lesser yellowlegs in English).

That’s not what Pointe du Toulinguet is called in Breton now, though – it’s Beg ar Garreg Hir. I can tell you that begmeans ‘beak’ or ‘point’ or ‘promontory’ (I’m tempted to say it’s ‘cape’ in Breton and make some wordplay, but that’s a bit of a journey, like Cape Breton Island, which is the place in Nova Scotia where ferries leave for Newfoundland). I can tell you that hir means ‘long’. As best I can discover, garreg is a mutated form of karreg, which means ‘rock’; you’ll see its reflexes in Welsh carreg and Irish carraig. So it’s Long Rock Point, or Long Rocky Point. With a hole for lesser yellowlegs off its tip. And the mirroring lighthouse on North Twillingate Island is on Long Point, which is rocky.

But the trail doesn’t end in Brittany. You can keep going, north across the channel to Britain. There’s a reason that Brittany (Bretagne) seems onomastically similar to Great Britain (Grande-Bretagne), and it’s that when the Anglo-Saxons came to Britain and made much of it into England, Celtic-speaking people were crowded to the edges – Scotland, Wales, Cornwall – or all the way across the channel, where they set up a little Britain for themselves, a bit of the familiar in a strange – and at length not strange – land.

And their strange name, toull inged, was made familiar by the local French: Toulinguet. And then that familiar name was applied to a strangely familiar place on the far side of the ocean. And then people from England – mostly from the southwest, Devon and Cornwall – came and saw that strange name and made it familiar, Twillingate. Such are the paths we take through willing gates and over the strange and familiar.