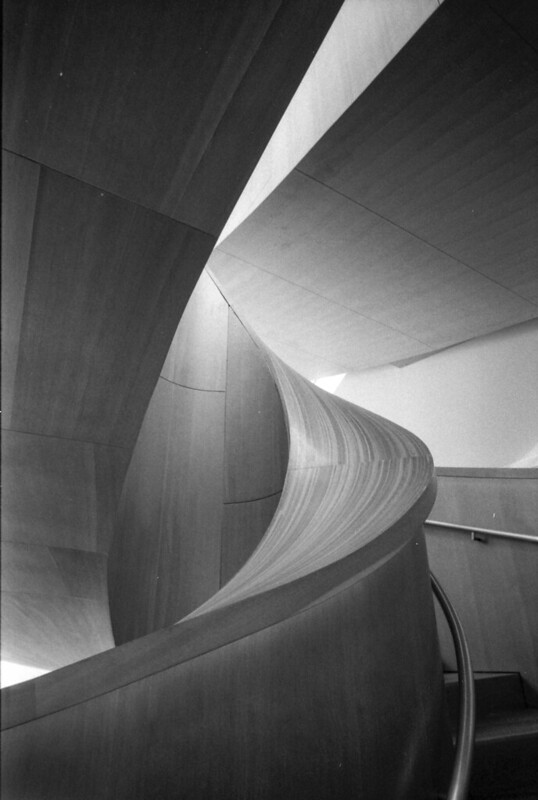

In the Art Gallery of Ontario, there is a staircase designed by Frank Gehry that swirls from the old lower parts to the new upper parts, ascending from floor 2 to floor 5. It is not merely spiral; it is a vortex of wood, an eccentric cycle, weaving through the air and through a glass ceiling too. You have a choice when going up from the merely modern to the very latest in the art world: you can take an elevator, rising straight and without view, as though the floors were swapped like cue cards behind the sliding doors, or you can climb step by step through the art whorl, seeing the building revolving as you exercise your prerogative and are in turn exercised.

The staircase suggests motion; it encourages motion; it sustains motion; and yet it is not motion. It is as unmoving as the people who stop on its steps for photographs. It is dynamic past and future, but still present. It whirled; it will whirl (or we will whirl while on it); but it is a whorl. It is whole, unbroken, containing an open hole.

Frank Gehry is famously fond of natural forms, and a whorl is natural enough, but it can also be artificial, whether artistic or not. There are many ways you may visualize a whirled piece. You may barely bend a forest’s worth of twigs to make a funnel to the sky, for instance.

You may curve strips of rolled steel into an abstraction of a whirlwind, a clone of a cyclone.

You may paint petals of fleering faces onto a wall, all encircling a void eye. Though your eye may avoid it, and your heart may reject it, it is an injection of art, nature denatured.

All are in the world of the whorl: if it is in some kind of concentric circles or spirals, it is a whorl.

Is whorl, the word, a frozen whirl? A whirl that was? In a convoluted way, yes. It is not a past tense of whirl – we have never said “I whirl today, I whorl yesterday” – but it is evidently formed from a variant of whirl; in earlier times, there were words whorwil and wharwyl that seem to have been especially swingy forms of whirl. This makes more sense when you know that whirl comes from something like whirvelen, likely from Old English hweorflian, a frequentative of hweorfan ‘turn’ (with the same frequentative suffix as gives us settle from set and prickle from prick). And it is also related to whirr and wharve.

And so it has turned around and come around again, and now it is concentrated, fixed in ink and pixels. But nothing stays still forever; the nature of nature is cyclic, and any whorl, too, may flower and grow and fade.

Or it may even ripple away in moments, waving as it passes.