Come see my etchings.

Well, not literal etchings. I just mean the epigrammatic epigraphs and autographs not so much engraved as gruffly roughed in on walls and other standing surfaces with spray paint and ink, occasionally chalk, rarely graphite. It depends on the graffitist and the graffito.

You do know, I assume – as you are highly literate and weirdly interested in words and their roots and branches – that graffiti is the Italian word for ‘etchings’. We are accustomed to treating it as a mass object, not just because it is objectionable to the masses but because it tends to come in quantity and variety and expanse – a graffitied wall is covered with paints, yes, but in the sum it is covered with paint; and so, be it scritti politici, be it tutti frutti, it is, like a plate of spaghetti, just so much graffiti. But it can be taken one graffito at a time; the artworks and taggings and plaints and quips and assorted other defacements are all done one at a time, just as posters are posted one at a time. And one piece of graffiti is one graffito.

Why? Because that’s the Italian singular. The verb is graffire, ‘engrave’ (or, yes, ‘graffiti’): io graffisco, tu graffisci, loro graffiscono; the past participle, ‘engraved’, is graffito or, in the feminine, graffita, and in the plural graffiti; and likewise an engraved thing – i.e., an engraving – is a graffito. If you wish to be waggish, take a sip of your martinus and call it a graffitus, but that was never a real word in Latin; Italian took its word from Ancient Greek γρᾰ́φω (grắphō, ‘I write, I draw, I etch’) – root of all those words that contain graph.

OK, but why would we call something that is painted ‘etchings’? Because before there was spray paint, there were things that scratched. First, I should say, ceramicists produced artworks on their pots by scratching through the glaze, and the result was called a graffito; but the various inscriptions on walls in Pompeii and Herculaneum, often sexual or scatological (“APOLLINARIS MEDICVS TITI IMPERATORIS HIC CACAVIT BENE”), were also called graffiti, and the term was also used for similar etchings at other archaeological sites. And so its use for more modern impromptu illicit mural inscriptions followed naturally.

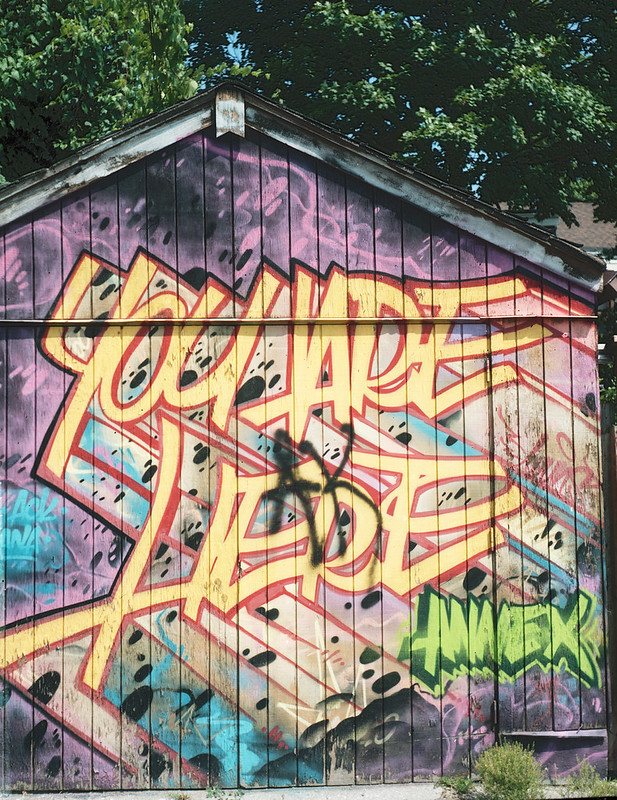

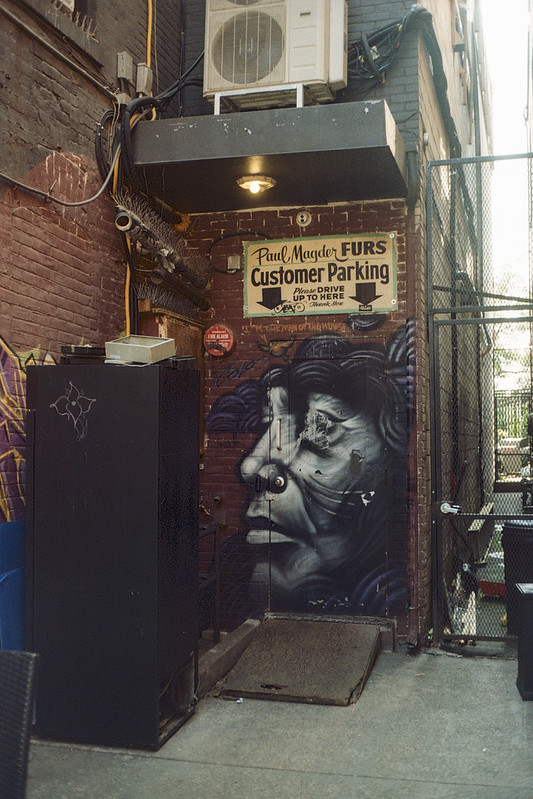

Now, I don’t blame you if you’re not so fond of graffiti. Not all of it is that great to look at, and if you’re the owner of the building affected and you didn’t ask for it to be there, you have a right to be disgruntled. But some graffiti – especially washroom writings – is witty: Nigel Rees put out five books of collected graffiti in the 1980s, and I bought all of them and read each multiple times, and have gotten some of my favourite witticisms from them. And some graffiti is vibrant and lively and a welcome addition to derelict buildings, longstanding hoardings, and sometimes the walls of people who have invited the artists. A few years ago I put together a book of my own photographs of that kind. Here are a few of my favourites.