When the summer air near the shores of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie starts to thread with coolness, and the Concord grapes grow heavy, and the leaves start to shiver and fade a little, my mind slips back to when I would drive down to Gerry, New York, and visit my grandmother, who has been gone more than a decade now. There is no cure for old memories, loss, and nostalgia, but there are prescriptions, and I have one here:

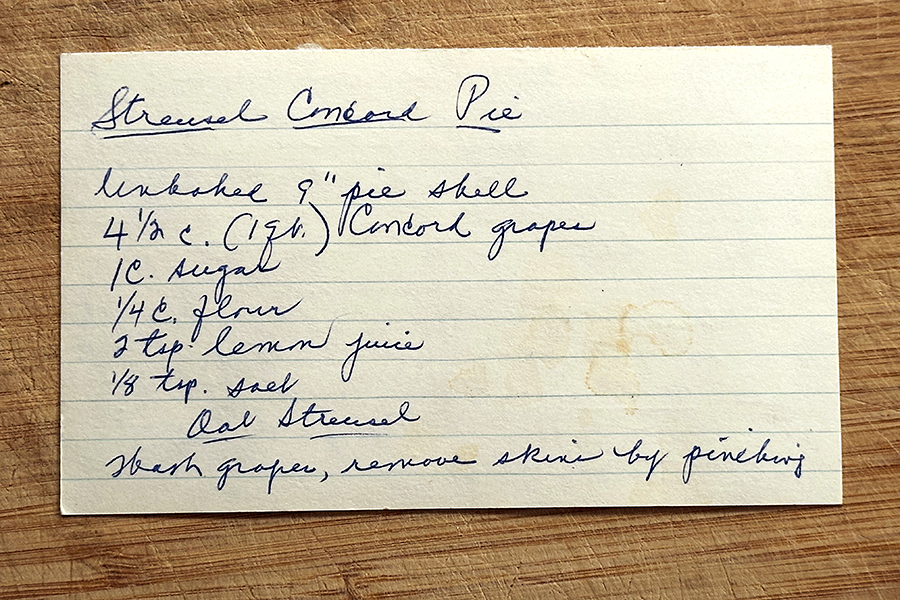

Streusel Concord Pie

Unbaked 9″ pie shell

4½ c. (1 qt.) Concord grapes

1 c. sugar

¼ c. flour

2 tsp. lemon juice

⅛ tsp. salt

Oat StreuselWash grapes, remove skins by pinching end opposite stem. Remove skins.

Place pulp in saucepan, bring to boil, cook a few minutes until pulp is soft. Stir often. Put thru strainer while pulp is hot, to remove seeds. Mix with skins. Stir in sugar, flour, lemon juice, salt.

Place mixture in pie shell. Sprinkle on Oat Streusel. Bake at 425° for 35–40 mins.

OAT STREUSEL: Combine ½ c. minute oats, ½ c. brown sugar and ¼ c. flour. Cut in ¼ c. butter or margarine.

The recipe does not add that, after eating a slice of the pie, you should smile at whoever you are eating it with so you can show your purple teeth. That is not part of the recipe that my grandma wrote out and gave to me. But it is part of the instructions I received from her when she served me pie at her kitchen table. This recipe will not bring back my grandmother, but it will recall her. Proust had his Madeleine; I have my Concord grape pie.

And I have many other recipes. I have quite a few cookbooks: the Larousse Gastronomique I received (on my request) for my fourteenth birthday; my own copy of the Better Homes and Gardens New Cookbook, my mother’s copy of which was so important to my culinary education; and a decent shelf full of others, the most used of which is probably How to Cook Everything by Mark Bittman. Several of them are ones I received as gifts, often from my cousin (on the other side of the family), who shares with me a love for food and wine and who (with the advantage of being much older than me) helped my education in the subject.

Humans have passed down instructions for preparing food since time immemorial, of course, and we have had cookbooks for centuries at least. Among the oldest extant cookery books is The Forme of Cury, dating to 1390, a new (and uncorrected) edition of which was published in 1780. I enjoy perusing its recipes for such things as “Pygge in sawse sawge,” “chykens in hocchee,” “Connyng in clere broth,” and “laumpreys in in galantine,” though I haven’t made any of them, in part because some of the ingredients and instructions (and the very English they’re written in) present a challenge for the modern cook. You can find a lovely collection of online versions of old cookbooks at MedievalCookery.com. Cooks nearly a half millennium ago (let us say ten grandmothers back – your grandmother’s grandmother’s etc.) set down instructions such as these:

To make egges in moneshyne

Take a dyche of rosewater and a dyshe full of sugar, and set them upon a chaffingdysh, and let them boyle, then take the yolkes of viii or ix egges newe layde and putte them thereto everyone from other, and so lette them harden a lyttle, and so after this maner serve them forthe and cast a lyttle synamon and sugar upon thẽ.

How big were the dishes of rosewater and sugar? The person who wrote this down surely knew. And surely knew when the appropriate occasion was to serve this, and who would enjoy it, and how. That was understanding that was received in person and through experience, though not written down as part of the recipe.

There was, naturally, a great diversity of foodstuffs. Take this, if you have the guts:

Garbage.— Take fayre garbagys of chykonys, as þe hed, þe fete, þe lyuerys, and þe gysowrys; washe hem clene, an caste hem in a fayre potte, an case þer-to freysshe brothe of Beef or ellys of moton, an let it boyle; an a-lye it wyth brede, and ley on Pepir an Safroun, Maces, Clowys, and a lytil verious an salt, an serue forth in the maner as a Sewe.

Junk food had a different valence in the 1400s.

As you read these recipes, you get to know the general style of the cooking of the time, which favoured a few spices (such as galangal, saffron, cinnamon, cloves, and pepper), tended to rely on boiling and baking, and used more sugar than you might expect. A recipe typically ended with the instruction to serve it forth (in more recent times, that seems to go without saying). And one more thing they had in common: these recipes were not recipes.

By which I mean they were not called recipes. It was only in the early 1600s that instructions for cookery were commonly called recipes; starting slightly earlier, they were called receipts, a usage that persisted to some degree in British English until quite recently. The term recipe did exist in English before that, but it was used first for such sets of instruction as these:

Take half a handfull of Rue a handfull of isop ix fygges gardynn mynttes a handfull & boyll all thise in a quart of condyte water with thre sponefull of hony & skym it clene then streyn it thorugh a clen cloth into a close vessell & drynk therof half a pynt at ones blod to arme so contynue to it be done.

Here is a translation provided by Margaret Connolly, the author of the article from which I got this recipe:

Take half a handful of rue, a handful of hyssop, 9 figs, and a handful of garden mint. Boil all these in a quarter of water from the conduit with 3 spoonfuls of honey and skim the liquid, then strain it through a clean clothe into a vessel and seal. Drink half a pint at once to fortify your blood. And continue until it is finished.

It is a recipe, yes, and it involves things you would eat as food, yes, but in this case it is meant to treat a medical problem. We’re not at grandma’s table for dessert, not this time. But these were the original recipes, because they were the first kinds of things for which was written Recipe – Latin for ‘receive’: this is what the apothecary will prepare and you will receive. Over time, this word Recipe came to be abbreviated as a simple R with a long tail and a line across it: ℞. These days it’s usually written Rx, though there’s no x, not any more than, say, there’s a letter I in $.

This is also why recipes have been called receipts: originally, a receipt was a thing or amount received; it could be money or property, or it could be a medical preparation. Over time, as we know, the word has mainly – though not exclusively – come to be used for the record of the receiving. But we received receipt as a word for a formula, with ingredients and instructions, and it had considerable shelf life. And recipe persists, along with the decocted grammatical stylings of the genre, which originated on the bench with the chemist’s crucibles.

The spread of recipe from the apothecary to the kitchen was not even a leap. In medieval times, there was not such a sharp division between the medical and the culinary; the things that you took to make you healthy were, by and large, things that you also ate to keep you healthy, though in different combinations and servings. The restorative value of food is recognized even in the word restaurant (from the French for ‘restoring’), which named first a restorative beverage or soup, and then transferred to the places that served such. And while we in Canada and the US today can readily buy many kinds of food (including junk food) at most drug stores in sections separate from the pharmacy counter, in times past the foods and drugs were not even administered separately. Remember even the fairly recent beginning of Coca-Cola, in 1886: as a health tonic served up by the druggist, originally containing cocaine as an active ingredient.

Consider this comment from the 1774 book Domestic medicine; or, A treatise on the prevention and cure of diseases by regimen and simple medicines ; With an appendix containing a dispensatory. For the use of private practitioners, by William Buchan:

CONSERVES AND PRESERVES.

Every apothecary’s shop was formerly so full of these preparations, that it might have passed for a confectioner’s warehouse. They possess very few medicinal properties, and may rather be classed among sweetmeats, rather than medicines. They are sometimes, however, of use, for reducing into boluses or pills some of the more ponderous powders, as the preparations of iron, mercury, and tin.

Then turn the page and read this recipe:

Conserve of Red Roses.

Take a pound of red rose buds, cleared of their heels; beat them well in a mortar, and, adding by degrees two pounds of double-refined sugar, in powder, make a conserve.

After the same manner are prepared the conserves of rosemary flowers, sea-wormwood, of the leaves of wood-sorrel, &c.

The conserve of roses is one of the most agreeable and useful preparations belonging to this class. A dram or two of it, dissolved in warm milk, is ordered to be given as a gentle restringent in weakness of the stomach, and likewise in pthisical coughs, and spitting of blood. To have any considerable effects, however, it must be taken in larger quantities.

The compounding apothecary would not, perhaps, say “Recipe” when giving you this preparation. But when you paid, you might get a receipt. And if you receive a dram or several of it, I think you might feel better.

Most of the things you will receive now when you hand a pharmacist a prescription have little or nothing to do with what you will receive when you order in a restaurant. But the heart of health is the kitchen, and many a recipe is a key to a healthy heart. I am happy that my grandmother pre-scribed her recipe. It was indicated as a memory aid, and it does help me to recall her; and on preparing and receiving it, I am – and in a way, she is – restored.