I have something special today. A special book from my bookshelf – well, aren’t they all – but this one calls for a special lens on my camera to photograph it.

The lens is an ordinary enough lens by description: 50mm f/2. There are quite a few of these out there, and 50mm f/1.8, and 50mm f/1.4. The f/2 maximum aperture may stand out for some because two of the most revered lenses in photography, the Leica Summicron and the Zeiss Sonnar, use it.

This lens is not one of those.

Not quite. After World War II, the Russians and their proxies took over some German lens factories and their designs, though not necessarily their production standards. This lens is a Russian copy of a Zeiss Sonnar. It’s called Jupiter-8. It cost me well under $100 on ebay a couple of years ago. It’s uncoated, prone to flare and not very contrasty, and tends to do interesting things with colour, especially when I adjust the files to recover some contrast.

Which makes it a favourite of hipsters. In fact, a remake of it is now being released. I’m not sure why; you can still get an original for well under $100 on ebay. But whatever. Some people like to revive old, questionably made translated copies. They have some charm, after all.

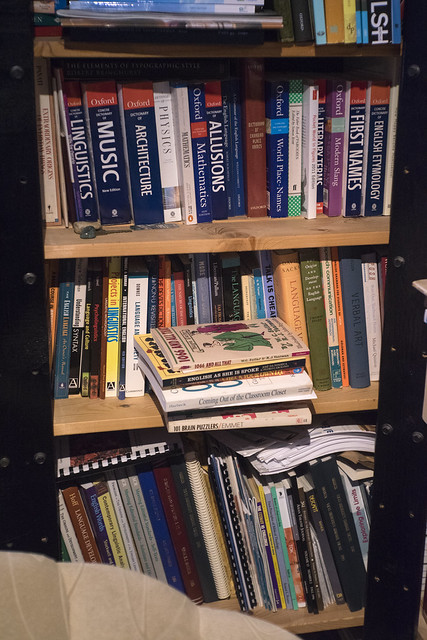

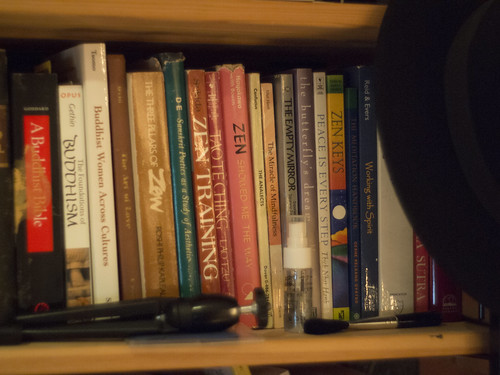

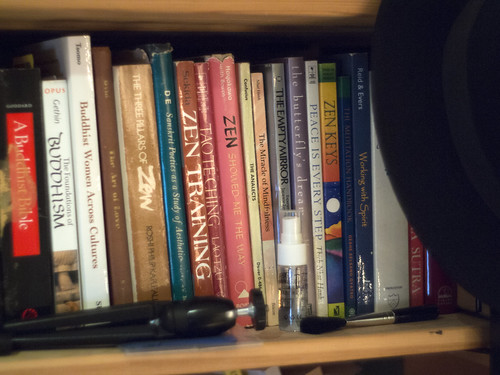

Now. Let’s look at my bookshelf. The part in the corner behind the chair. As you can see, it’s so full I have started stacking books in front of the standing books.

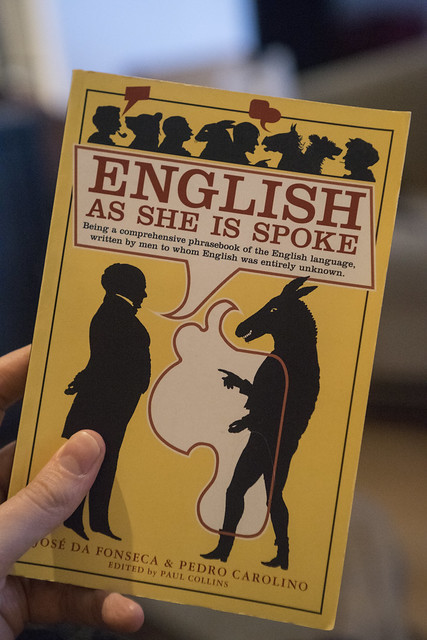

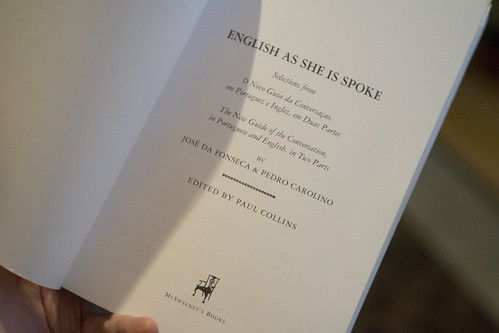

Here’s the one I want. It’s a reprint of a classic that I first read about years ago.

The author, Pedro Carolino, set out in 1855 to make an English phrasebook for Portuguese speakers. He was a native speaker of Portuguese. He did not speak English at all. He also did not even have an English-Portuguese dictionary. But he did have a French-English phrasebook and a Portuguese-French dictionary. Why wouldn’t that work just fine, eh? Find the equivalent word and slot it in.

Ha ha ha.

It was so classically awful, Carolino had made himself the Ed Wood of translation. The book was subsequently reissued under the title English as She Is Spoke for the amusement of all and sundry.

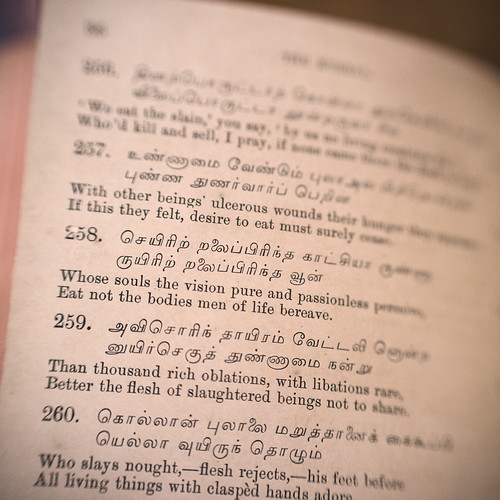

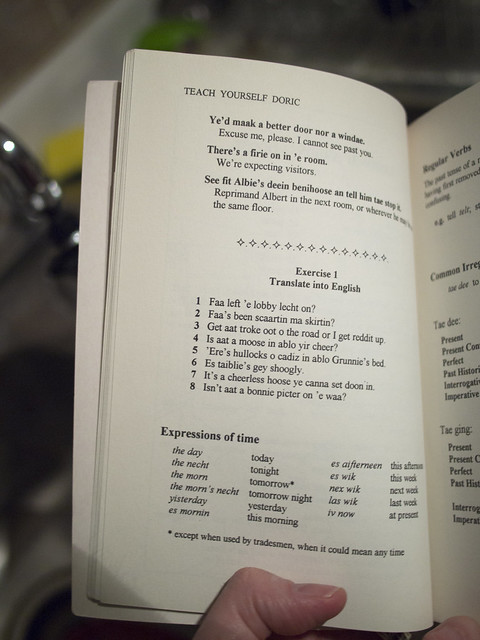

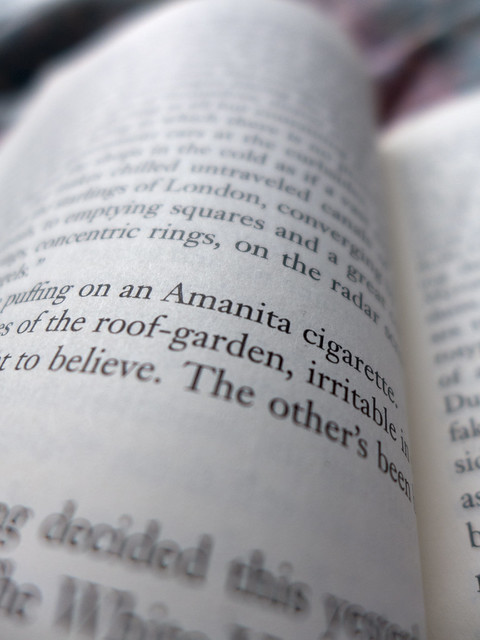

How bad is it? Here, read.

You see, it’s not just that the translations are awful, it’s that some of the things that are being said are quite iffy too.

The crowning glory, however, is the last section.

And its greatest moment, surely its most quoted line, comes at the very end of this edition.

To craunch the marmoset.

This may sound like something one does at brunch, but it is presented as a translation of Esperar horas e horas, which means ‘To wait hours and hours.’

So we have three questions. First, what is craunch? Second, what is marmoset? Third, how on earth did he get from Esperar horas e horas to To craunch the marmoset?

Number one, then: craunch. Does it sound like crouch? Understandably, but that’s not quite it. How about crunch? Yes, there we are. It has alternate form cranch, which has related form scranch, which has 16th-century Dutch cognate schranzen ‘split, break’, which has become modern Dutch schranzen ‘eat greedily’. To craunch a marmoset means the same as to crunch a marmoset.

Number two: What is a marmoset? It is a small simian, a funny little long-tailed monkey. Johnny Carson had one of his classic moments on The Tonight Show when one of them relieved itself on his head:

Does marmoset sound like it should be a marmot or some similar rodent? The words marmot and marmoset are almost certainly related. A marmot is, in French, une marmotte. The word marmot now refers to a small child, but it used to refer to a monkey. Both words seem to come from the same root as murmur, though it’s not entirely established (but it may be spoken of quietly). The diminutive form of marmot came to English as a name for this little monkey, marmoset.

They don’t call marmosets marmosets in French, though. They call them ouististis, a word formed in imitation of a sound they make. That word shows up in an idiomatic phrase as well: un drôle de ouististi. I am assured by my Collins Robert French-English dictionary that that means “a queer bird” – I suspect we would now say an odd duck to mean about the same thing.

Speaking of idiomatic phrases, if I open my Le Robert Mini, which is entirely in French, I find at marmot that there is an idiom meaning “attendre longtemps” (‘wait a long time’): croquer le marmot.

Remember how Carolino made his book? He used French as an intermediary.

Having found that croquer le marmot meant, in Portuguese, esperar horas e horas, what remained was to translate it into English: croquer became – well, it should have become crunch or munch, but I guess he liked craunch better; marmot became marmoset, because marmot could be translated thus as easily as croquer could be translated craunch (and anyway it didn’t mean ‘marmot’ in the English sense of ‘big squirrel-like critter’).

This, however, leaves us with another question: What does crunching a marmot or marmoset or monkey or small child have to do with waiting for a long time? Does it just take hours to eat one?

I’ve gotten the answer from a couple of handy French reference sites. The first is the eminently useful Wiktionary. The second and more detailed on this point is Expressio.fr. Both of these are in French, so I will just tell you the answer here in case you don’t easily read French or can’t be bothered. In times bygone (up to a half millennium ago), doorknockers on French dwellings (that had them) were often done in the style of grotesque figures like monkey heads, and so they came to be called marmots. In that same time period, croquer was used to mean ‘knock, hit’. So croquer le marmot meant ‘knock at the door’, and by implication ‘stand outside the door waiting and knocking’. And thus ‘wait hours and hours’.

At last. I bet you’ve been craunching the marmoset for that little explanation, eh? Well, it’s one for the books now, by Jupiter.