I’m on the scent of another word from the bookshelf. Let’s look back here in the dark hidden corner behind the baseball-glove chair.

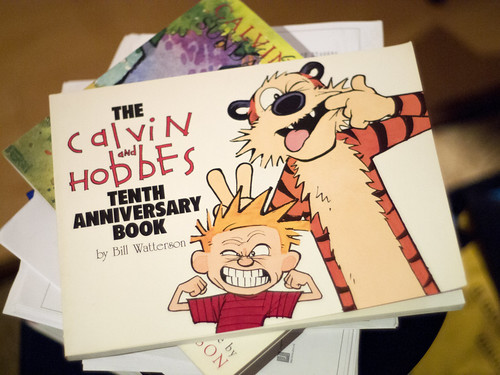

Tall, thin, graphic, glorious mementoes of my youthful favourites. Let me tug this one out and drop it on the stack next to the chair.

Does it look familiar as I gradually reveal it? It was a revelation to me 30 years ago.

The book is actually 20 years old. It came out in 1995. It’s The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book. Meaning that Calvin and Hobbes started 30 years ago.

30 years ago today, in fact. November 18, 1985. I’m not one to choose a single favourite in most things, but Calvin and Hobbes is easily my favourite comic strip. Intelligent. Well drawn. With a few simple lines Bill Watterson could express so much character. And then sometimes he’d really go to town.

The strip draws on the impermanence of childhood and the perdurance of childishness. It revels in the ridiculousness of life and luxuriates in ludicrous fantasy, all forever contained and threatened by parents, protectors, and peers who insist on imposing order, stifling imagination, rebuking rambunctiousness. Never mind: for the duration of a strip we may strip ourselves of due ration and see things as… well, as they really are, honestly. (To see the images closer up, by the way, click on them.)

Does Calvinball seem a senseless sport? You’re playing it right now. English is the Calvinball of languages. All natural languages are Calvinball to some extent: we make up rules as we go along, sling slang, even with straight faces collude in ludic creations that come and go with the breezes. There will always be those who try to nail it all down, stop it from changing, paint pretentiousness on the messy pretense, but there will also always be us Calvinist-Hobbesians. And a little Calvinist-Hobbesian in all of us, even the sourest, wafting in and out. Nothing stays the same, of course, but then, nothing stays the same.

Some of us like our play cerebral, very cerebral, even punishingly, showoffishly cerebral. The play of the art gallery placard. The play of academic essays (every word of Derrida and Baudrillard is a game – actually, every word of everything is a game, but some academic word games are like playing racquetball with razors for racquets and kittens for balls). Watterson happily took the piss out of those games while playing them athletically and commenting on life in passing. If thoughts are a penny each, Watterson gives you seven cents.

Calvin and Hobbes is the only comic strip I can recall having learned a word from in my adult life. I admit my memory my be of uneven focus; perhaps I learned the word first and the shortly after saw it again in the strip. But what other strip (well, aside from xkcd) would you find a word like this in?

Evanescence. The sound of a snake s and two soft sickles c c cutting down with ease and taking away. A play of six letters dancing to make eleven letters, here now and moved on in the next moment, melting as they appear. If life never makes any sense, if it is vain and in vain, it is because it is vanishing. Nothing lasts, so there is a last of everything. Just as words can flip their sense inside a sentence, so too our innocent sentience, even our essence, self-incinerates in an instant.

Where does this word come from? Page 166 of the book, yes, but that’s the medium. Before that? First we trace evanescence to English evanesce ‘fade away, vanish into thin air, disappear, be effaced’; then we trace that to Latin evanescere, which contains e ‘out’ (as in E pluribus unum) and vanescere ‘vanish’, which in turn comes from vanus ‘empty, insubstantial’ – the etymon of vain as well as vanish. The Latin equivalent of Japanese mu, the central concept of Zen, so often translated as emptiness but that’s misleading. There is nothing there, yes, but it’s because as soon as you look there there is no there there anymore. Everything is always waving goodbye because everything is always a wave, impermanent, waiving permanence, invincible only because there is nothing to vanquish: it has vanished.

But that is not bad. That is just as it is. Our lives are like a stroll across a paper suspension bridge, dropping lit matches behind us. Everyone walks in time and then runs out of time. In the road trip of life, how often do we see when our touring machine will halt? When I bought this book, did I know that a decade and a month after Calvin and Hobbes had begun it would end? The strip evanesced in December 1995, the eternal six-year-old setting off into eternity with his tiger, and Watterson flowed away invisibly, liberated. No new Calvin and Hobbes strips have been drawn in 20 years. And yet there it still is. It left its marks. They have not finished fading yet.