Maury’s Icelandic friend Brandur is quite the firebrand. As I entered Domus Logogustationis, he was brandishing a book and a bottle of Bas-Armagnac and shouting – in a style perhaps more of Russell Brand than of Marlon Brando – “What. Is. This. Word. Brandywine!”

I approached Maury and leaned close. “Is he on a bender?”

“No,” Maury said. “In fact, we were just about to have the first cocktail of the evening. A Berlin.”

“Ah, yes, a splendid beverage, though best had second.”

“We’re out of vermouth,” Maury said.

Brandur slapped down the book, which was a cocktail manual. “Look!” It listed the ingredients for a Berlin as “1 part Becherovka, 4 parts brandywine.”

“How very quaint,” I said.

“Do they think they’re Tolkien?!” Brandur exclaimed.

“Perhaps in a token way,” I said.

“I just want to know,” Brandur said, “is brandywine redundant, or is it a contradiction in terms? After all, brandy is not wine. But it’s made from wine.”

“It’s just the long form,” I said. “The short brandy was clipped from it, or else it was clipped and altered from the Dutch source, brandewijn, of which brandywine is a somewhat anglicized version.”

“At least it’s made from wine,” Maury chipped in. “Unlike that caraway-flavoured vodka with which you Icelanders get carried away.”

“Brennivín!” Brandur said.

“Same word,” I said. “In origin. Imported into Iceland, and localized; the liquor it names was not so easy to import, and impossible to make with domestic crops, and so the spirits were also localized. But, yes, brandewijn means ‘burnt wine’ or, more broadly, ‘cooked wine’.”

“And as brandywine and brennivín have the same origin,” Maury said, “so too does Brandur.”

“What!” said Brandur, brandishing the book. “My fine name refers to a burning log, or a sword!”

“Yes,” I said, “all from the same root. The Proto-Germanic *brinnaną, meaning ‘burn’ or ‘be on fire’, gave us English burn and its assorted Germanic cognates, such as German brennen, as well as brand, which started as a word for a burning log or piece of wood – a firebrand – and came to name a hot piece of metal, such as is used for branding animals and barrels of spirits, and also a sword, flaming or otherwise. And it is from that weapon sense that the French verb brandir came, meaning ‘flourish a weapon’, and from that – which is conjugated nous brandissons, vous brandissez, et cetera – came English brandish.” I nodded to the book, which he was still wielding at head level.

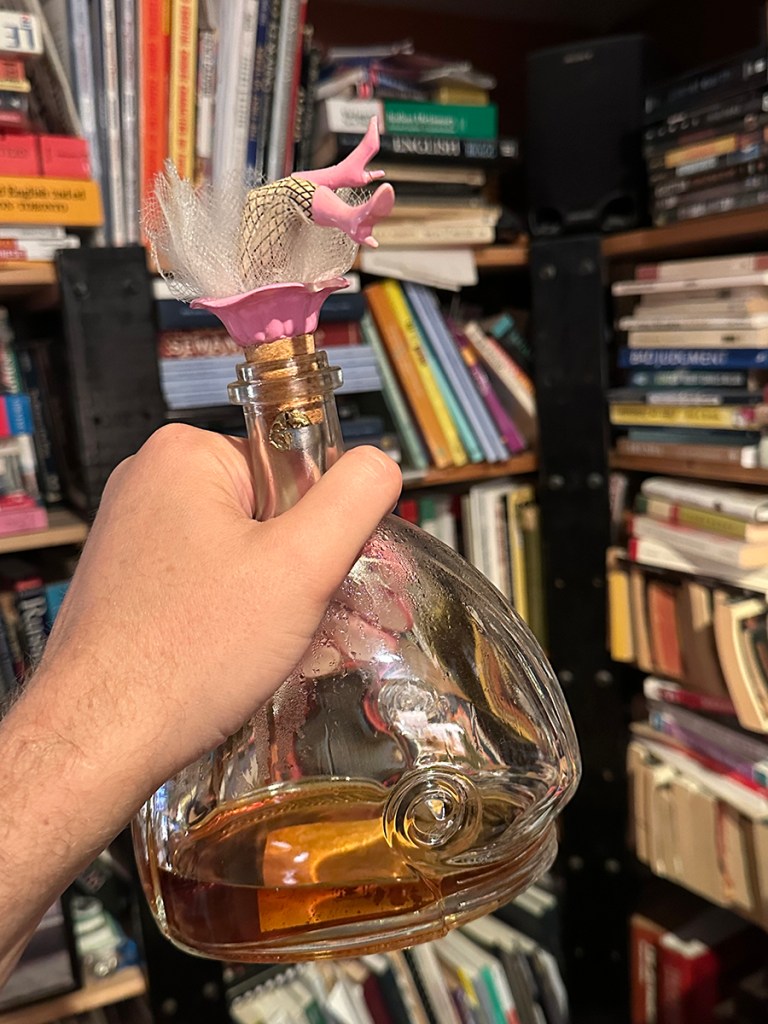

“And now,” Maury said, “let us lift our spirits another way, by pouring some of this brown river into this mixing vessel—” He began to free-pour the Armagnac into a cut-glass pitcher.

Brandur wagged a finger. “Ah, ha, I know what you did there. Brandywine, Brown River.” He turned to me. “In The Lord of the Rings, the Brandywine River’s name is a reanalysis of baran duin, ‘brown river’.”

“Or, in the real world,” I said, “baran duin was backformed by Tolkien, given that he had already given the river the name Brandywine and needed to come up with an in-world derivation.”

As Brandur and I chatted, Maury continued the mixing: he added an appropriate amount of Becherovka (Czech bitters, if you don’t know) and some ice, and stirred, and then strained it into three glasses. “Friends, the Berlin,” he said.

“So called because of the Brandenburg Gate?” Brandur said.

“That’s a rather clever connection,” I said. “Pity Brandenburg isn’t actually related to brandy.”

“It might be,” Maury said, raising a finger.

“Well, it might be,” I said, “but it might not. We’re not entirely sure. But that’s not why this cocktail is the Berlin. It’s so called for the same reason we ought not to be having it as our first drink.” I reached for the cocktail book, which Brandur had set face down open to the appropriate page, and showed him the epigraph on the recipe:

First we take Manhattan, then we take Berlin. —Leonard Cohen

“I see,” said Brandur. “And does it matter what brand of brandy one uses?”

“Cognac, Armagnac, but nothing cheap, please,” said Maury. “That would be disappointing.”

“Speaking of which,” I said, “where’s the garnish?”

“Withheld for safety reasons,” Maury said.

Brandur furrowed his brow and looked in the book. “Ah,” he said, and read aloud: “Orange zest, burnt.”