I promised to come back to this book. Remember? This bookshelf at my parents’ place?

This book.

I have it on my bookshelf too. Not the same edition. It’s back behind a post. See it?

Look closer.

A box set.

The set also contains The Hobbit, but the volumes of The Lord of the Rings are thick from being read, so I keep The Hobbit next to the box (I read it before I got this box set, so this copy is less read).

Did you know that books get thicker with reading? They absorb some of you each time you go through them. Every book you read, part of you is passed into it through your fingers and the pages are fattened with your spirit and imagination. Return to the book and you will find it there. And add some more. And as you pass through life, that soul you left in the book still feeds into you and sends images to you. You never truly say farewell to a book once you welcome it and it welcomes you.

I swear it’s true.

And I read this copy twice. At least twice, but twice for sure. So it’s thickened.

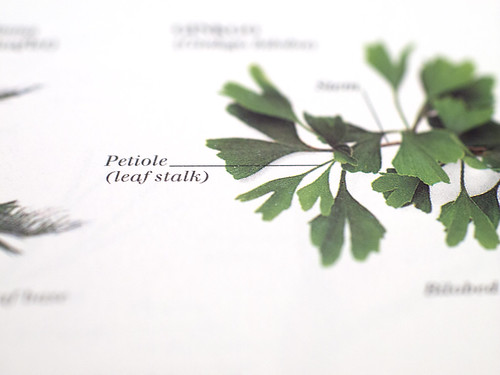

I like this edition because it has the appendix in the back with the alphabets, runic and Fëanorian.

I cannot tell you how much I fell in love with these alphabets in my childhood and youth. I loved alphabets. I once made a volume of fantasy languages; at that age, I couldn’t be bothered much with the syntax or lexis (let alone the morphology), but I came up with a complete sound system and alphabet for each of them. I’m sure I have that book somewhere. It’s a graph Nothing Book: a hardcover book with empty pages of graph paper. I filled quite a few of them.

I shall have to dig it out. If I have it here it’s under a hundred pounds of other boxes in the closet, probably. Not tonight.

Tolkien is famous for creating languages for his different races. He’s not the only person to create languages, of course; Klingon and Na’vi are two recent examples of thoroughly created “conlangs,” constructed languages (I find the term conlang a bit fanboyish – sci-fi fans have an absolute fetish for syllable acronyms – so don’t count on seeing me use it much). But he was one of the seminal ones to do so, and he did it in a truly thoughtful way, like the philologist he was: complete with history, sound and morphosyntax changes, and more.

Tolkien based his languages on human languages he liked. He like Welsh and he liked Finnish, and he created two elvish languages, one inspired by each. The language of the Grey-elves is Sindarin, inspired by Welsh. It’s the language that elves in The Lord of the Rings generally use in everyday use. But then there is the one based on Finnish: Quenya, the language of the High Elves, the ones who went to the west and for the most part stayed there. Some of them came back to Middle-earth and lived with the Grey-elves and came to speak Sindarin, but kept Quenya – a gradually changed dialect of it – as a formal tongue. The language of their home and heritage, brought out now for formal occasions. And for when they look to the west and their spirits are crying for leaving, remembering Valinor, the western land, and Valimar, its capital.

That might seem familiar to many people in Canada, children of immigrants, who speak English every day but, when they go to church on special occasions or to community gatherings, still have the language of their forebears, wherever they came from. The language that their parents, or their parents’ parents, said farewell to their native home in. The language that is at the same time the connection, the thread, that holds them to their homeland. The language they read the book of their heritage in, and that connects them to the part of themselves they left there.

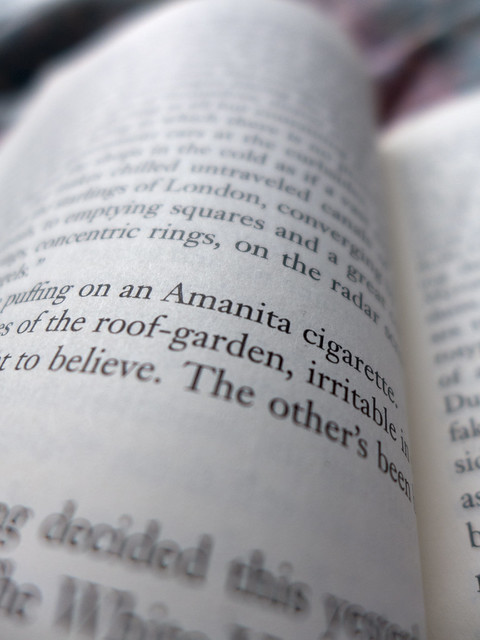

The longest text Tolkien wrote in Quenya is this poem – a song, actually:

That’s in the single-volume edition my parents have. Here’s in my edition:

He helpfully gives a translation of it below the text.

It’s in the first volume, The Fellowship of the Ring.

It’s sung by Galadriel as the company of the ring leave Lothlórien, the elvish tree-garden-river-home, a green dreamland. In fact, Lothlórien means ‘The Dreamflower’. If you saw the movie, Galadriel is the one played by Cate Blanchett, a rather perfect bit of casting. You can hear it sung in many versions on YouTube. Here’s one by Adele McAllister:

The name of the poem is also the word that comes around in the last stanza:

Namárië.

Four syllables: /na ma: ri ɛ/.

Namárië! Nai hiruvalyë Valimar.

Nai elyë hiruva. Namárië!Farewell! Maybe thou shalt find Valimar.

Maybe even thou shalt find it. Farewell!

You can glean quite a bit from even just this stanza. Nai means ‘maybe’; hiruva means ‘shalt find’; elyë means ‘thou’ and can be attached to the end of hiruva to make hiruvalyë ‘thou shalt find’ or can stand alone to be emphatic ‘even thou’; namárië means ‘farewell’.

Except there’s more you can’t see from that passage. Namárië comes from á na márië, which means ‘be well’. It is used not only for farewell but for greeting and welcome.

Be well. Go well. Fare well. But in English we say farewell only as a parting. We may say hail as a greeting, and that comes from a wish of good health. But we have lost the literal sense of both in our common use anyway. We may say Good day as a greeting and as a parting, but we only perfunctorily wish a good day if we think of it at all. I cannot say how sincere Tolkien’s elves were in their salutations; remember, this is a word in what had become for them a ceremonial language. It is as though we in English said Latin Salve in greeting and parting. Or, perhaps, Namaste.

But wellness is good, coming, staying, or going. And the road goes ever on. You travel through space and time, taking yourself with you and yet leaving yourself everywhere, and taking everywhere with yourself. There is some of you where you came from, some where you are, perhaps some already where you are going. And every meeting and well-wishing is also an acknowledgement of the unbridgeable distance between two persons, and the transience of our passage through that moment.

We are always everywhere we have been, and yet we are never completely anywhere: we carry our absences like wishing wells in our shirt pockets; we yearn for places we no longer are, places we’ve lost, places we have not yet been. We fatten the pages of the book of life, pages made from the trees of our lost and future homelands. We wish each other well. Namárië.