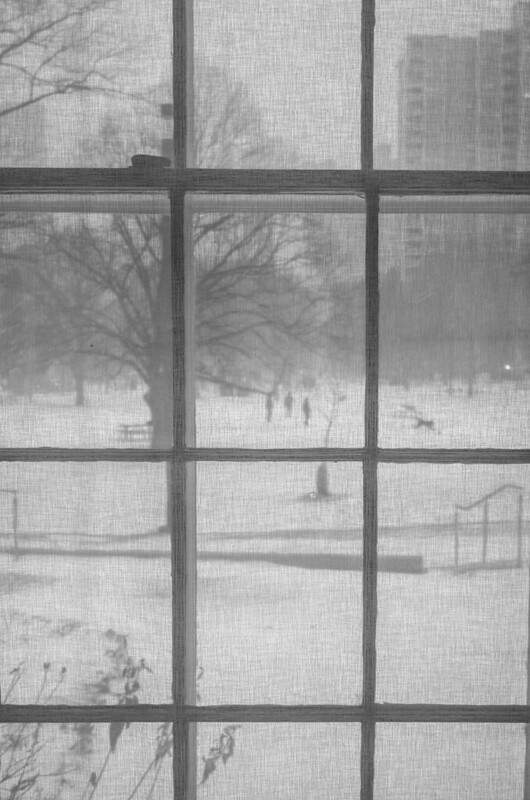

Do you have a dim view of gloom, or a gloomy view of dimness? Many people do; the gathering or already gathered dark is not everyone’s favourite. But I like the rise of the gloaming, the crepuscular turning from the sun, and the tenebrous hours that follow; it makes it so much easier to find the sources of light near you, and to delight in contrasts.

Gloom is a useful good old Anglo-Saxon word, descended from the Old English verb glumian ‘be gloomy’ – and yes, glum is related. But where glum is dull and dumpy, gloom looms and booms. It plays well for its sense: it has that gl- phonaestheme associated with visual things (more often gleaming and glittering, though), and it has several rhyme partners – the top three most used can all be found in George Santayana’s “Sonnet XXV”:

As in the midst of battle there is room

For thoughts of love, and in foul sin for mirth;

As gossips whisper of a trinket’s worth

Spied by the death-bed’s flickering candle-gloom;

As in the crevices of Caesar’s tomb

The sweet herbs flourish on a little earth:

So in this great disaster of our birth

We can be happy, and forget our doom.

Occasionally a few other rhymes show up:

O gardener of strange flowers, what bud, what bloom,

Hast thou found sown, what gathered in the gloom?

—Algernon Charles Swinburne, “Ave Atque Vale”At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

—Thomas Hardy, “The Darkling Thrush”Splendidly lambent in the Gothic gloom,

And stamened with keen flamelets that illume

The pale high-altar.

—Edith Wharton, “Chartres”

You can see how often it is used for contrast, juxtaposed with something bright or pretty. It’s sometimes paired with gleams, as for instance in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “My Lost Youth”:

I remember the gleams and glooms that dart

Across the school-boy’s brain

And Algernon Charles Swinburne really goes to town in “Nephelidia”:

Gaunt as the ghastliest of glimpses that gleam through the gloom of the gloaming when ghosts go aghast?

But even without the rhymes, it seems to beg for something far less sombre to contrast with it:

In the gloom of the deepening night take up my heart and play with it as you list. Bind me close to you with nothing.

—Rabindranath Tagore, (“Keep me fully glad…”)Into the gloom of the deep, dark night,

With panting breath and a startled scream;

Swift as a bird in sudden flight

Darts this creature of steel and steam.

—Ella Wheeler Wilcox, “The Engine”

And, at last, it partakes in playtime, as with T.S. Eliot in “Whispers of Immortality”:

The sleek Brazilian jaguar

Does not in its arboreal gloom

Distil so rank a feline smell

As Grishkin in a drawing-room.

Gloom, we see, is not simply an absence of light; it is an invitation of light. You know that the gloom will at some time, in some way, be relieved, be it by candle, or lamp, or lambent moon, or the dawn’s early light. Or by simply making light, as Edna St. Vincent Millay found in “The Penitent,” which (by grace of the sunsetting of copyright) I will present in full:

I had a little Sorrow,

Born of a little Sin,

I found a room all damp with gloom

And shut us all within;

And, “Little Sorrow, weep,” said I,

“And, Little Sin, pray God to die,

And I upon the floor will lie

And think how bad I’ve been!”Alas for pious planning—

It mattered not a whit!

As far as gloom went in that room,

The lamp might have been lit!

My Little Sorrow would not weep,

My Little Sin would go to sleep—

To save my soul I could not keep

My graceless mind on it!So up I got in anger,

And took a book I had,

And put a ribbon on my hair

To please a passing lad.

And, “One thing there’s no getting by—

I’ve been a wicked girl,” said I;

“But if I can’t be sorry, why,

I might as well be glad!”